There are wrestlers who burn bright, and there are wrestlers who burn slow. Then there’s Bryan Clark — a man who seemed forged in the molten core of late-80s wrestling excess, survived the fallout of the ‘90s boom, and emerged from the wreckage of WCW and WWF with something most of his peers didn’t: perspective. He was The Nightstalker, Adam Bomb, Wrath, and half of KroniK. Four names. Four eras. One man who could powerbomb a small planet and look good doing it.

The Nightstalker Rises

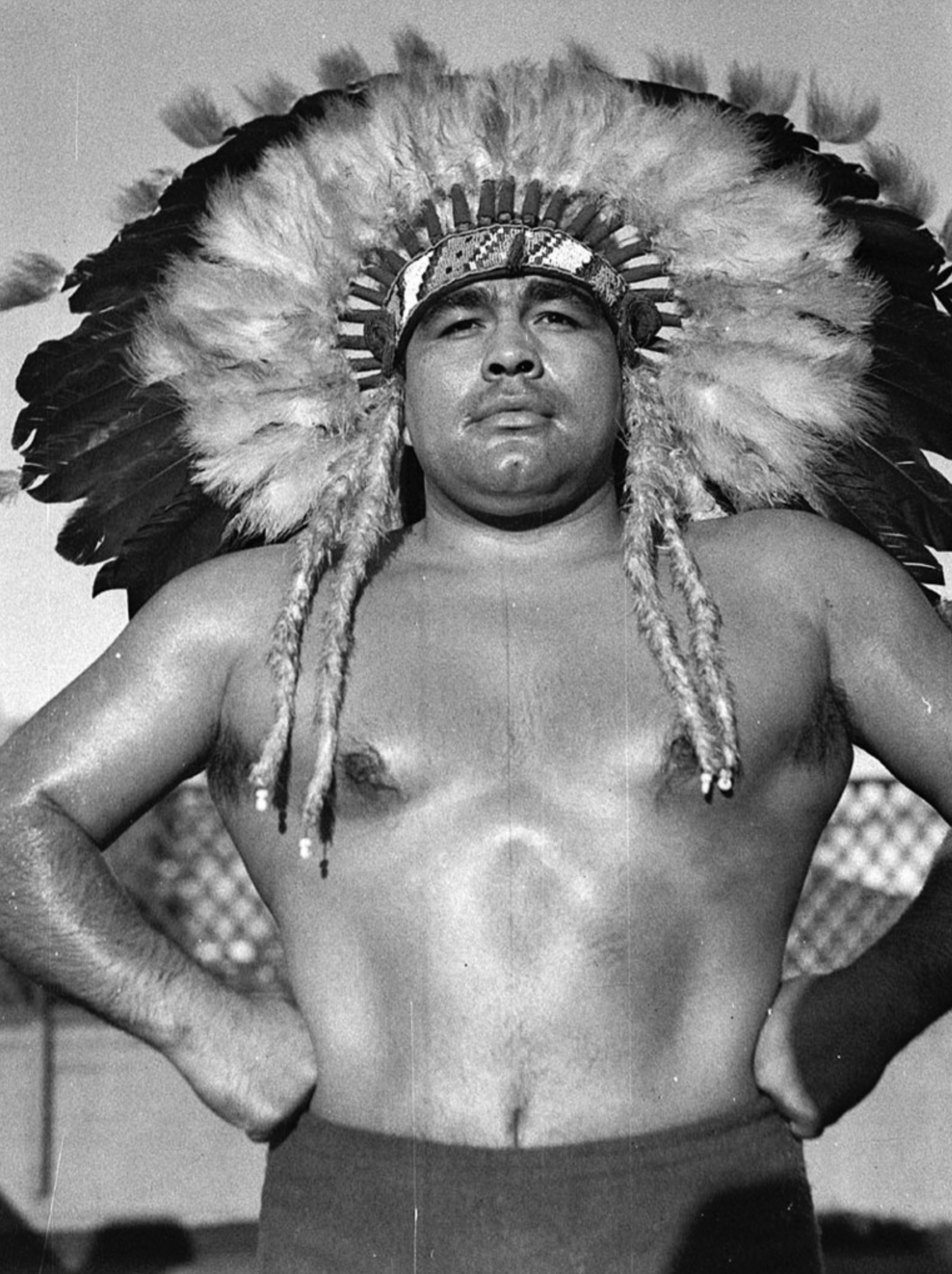

It started in the late ‘80s, when wrestling was as neon and greasy as a Daytona Beach arcade. Clark, fresh from the Air Force and built like a drive-in movie monster, was molded into The Nightstalker. Managed by Ox Baker — whose eyebrows alone could frighten livestock — Clark prowled the American Wrestling Association like a slasher movie come to life. Face paint? Check. Oversized hatchet? Double check. Promo segments with Ox barking threats that sounded like demonic bedtime stories? Absolutely.

The AWA was circling the drain, but for a moment, The Nightstalker looked like the future — six-foot-six of menace, cutting promos with all the conviction of a man who could actually follow through on them. He wasn’t just a monster heel; he was the kind of guy who made kids in the front row drop their nachos and run for cover.

Clash and Burn in WCW

When the AWA collapsed, Clark moved to WCW, that chaotic southern carnival of mullets and muscle. He debuted on WCW Saturday Night, stomping through enhancement talent like they owed him money. Within weeks, he was fighting Sid Vicious at Clash of the Champions XIII, then teaming up with The Big Cat in what might be the most intimidatingly named duo that never quite got off the ground.

WCW at the time was like a three-ring circus run by drunk ringmasters — too many gimmicks, too many egos, and not enough direction. Clark’s Nightstalker was a victim of that chaos. One week he was a rising star, the next he was a masked “ghoul” at Halloween Havoc. It was wrestling’s version of being demoted from linebacker to mascot.

But the man didn’t quit. He just waited for the right radioactive moment.

The Birth of the Bomb

By 1993, the WWF was looking for something — anything — new. The steroid scandals had deflated the muscle gods, and the new era needed color, gimmicks, and a wink at the camera. Enter Adam Bomb: a man literally irradiated by the Three Mile Island disaster, complete with glowing contacts, hazard symbols, and a manager who looked like he’d wandered out of a Duran Duran video.

It was absurd. It was loud. It was perfect for the early ‘90s.

Clark threw foam “nuclear missiles” to the crowd like he was arming an army of eight-year-olds. He came to the ring as if the Chernobyl core had grown biceps. Underneath the radioactive schtick, though, was something that made him stand out — a ring presence that was surprisingly athletic for his size. He could move, he could bump, and he could sell, three things not every giant in Vince McMahon’s toy chest could do.

Still, Adam Bomb was cursed with a mid-card fate. He was a villain, then a hero, then cannon fodder for the likes of Earthquake. Fans loved the look, the charisma, and the cool merch — but storylines in that era were about as coherent as a fever dream. Clark’s frustration was inevitable. When promised opportunities vanished like fallout dust, he walked.

He later said it wasn’t the character he hated — it was the system. The paychecks didn’t match the miles, and the Intercontinental Title run he’d been teased with never came. By 1995, the Bomb had detonated his bridge to Stamford.

The Wrath of Clark

Then came Wrath. If Adam Bomb was a cartoon, Wrath was the dark reboot. When Clark reemerged in WCW in 1997, he looked like a Mortal Kombat boss who’d wandered into Monday Nitro by mistake — black armor, menacing glare, and a finisher called The Meltdown that looked like it could rearrange vertebrae.

He teamed with Mortis (played by Chris Kanyon, one of wrestling’s most inventive minds) under the guidance of James Vanderberg in the Blood Runs Cold storyline — WCW’s attempt to blend martial arts fantasy with wrestling realism. It was weird, stylish, and pure ‘90s. The crowd didn’t always get it, but Wrath carved his space as the quiet killer in a company overrun by egos in denim vests.

When he broke away from the gimmick, Clark reinvented Wrath as a solo powerhouse. He didn’t need smoke machines anymore — just his strength and that devastating finishing move. He racked up an undefeated streak, beating names like Meng and Glacier, and for a time, WCW fans whispered his name in the same breath as Goldberg’s. But the company that could never see the forest for the storylines broke the streak before it could mean anything, feeding him to Kevin Nash.

WCW giveth. WCW taketh away.

KroniK: Heavy Metal Tag Team Chaos

If Wrath was Clark’s lone-wolf era, KroniK was his symphony of destruction. In 2000, he joined forces with Brian Adams — another powerhouse often stuck in creative purgatory — and the two became a tag team that looked like they could’ve bench-pressed an SUV just for fun. With matching black gear, massive physiques, and names that sounded like a nu-metal album, they were instantly iconic.

KroniK didn’t play around. They weren’t comic relief or mid-card filler. They were mercenaries, literally — WCW booked them as hired guns who’d take out anyone for the right price. It was a perfect concept for two wrestlers who’d seen the business chew up better men and spit them out.

They won the WCW World Tag Team Titles twice, dominated the Natural Born Thrillers, and even tangled with Goldberg himself. When WCW was sold to WWF, KroniK followed — only to find that the new bosses weren’t exactly rolling out the red carpet. A single pay-per-view match with The Undertaker and Kane at Unforgiven 2001 went poorly, and the duo was cut loose soon after.

But for all the politics and mishandled angles, KroniK remains one of wrestling’s great “what if” teams. They looked like the future of tag-team dominance — a hybrid of athleticism, power, and presence that predated the “realist” wrestling boom by a decade.

The Last Round and the Long Road Home

After the WWF let them go, KroniK went global, working in Japan’s All Japan Pro Wrestling, where they captured the World Tag Team Titles in 2002. In Japan, where power and intensity are revered over theatrics, KroniK thrived. But injuries began to pile up, and by 2003, both men hung up their boots.

For Clark, the physical toll of years in the ring — surgeries, bruises, and broken bones — was the price of chasing glory in an industry that never gave guarantees. He went from headlining WCW pay-per-views to fighting his own body in recovery rooms. Yet when you talk to him, there’s no bitterness, just a sense of having lived a dozen lives in one.

Fallout and Redemption

In later years, Clark’s name resurfaced in headlines — a class action lawsuit against WWE over concussions, later dismissed, and legal troubles that were ultimately thrown out. Through it all, he remained grounded, often crediting his military discipline and years in wrestling for teaching him how to weather any storm.

Ask him today what meant the most, and he doesn’t mention the titles or the TV time. He mentions Brian Adams. The bond they had in KroniK was real — forged in pain, brotherhood, and mutual respect. When Adams passed away in 2007, Clark called their partnership “the highlight of my career.” You believe him when he says it.

The Legacy of Bryan Clark

In the world of professional wrestling, image is everything — and Bryan Clark was a man of a thousand images. The painted madman with the hatchet. The nuclear monster. The demonic warrior. The hired gun. Each reinvention carried a piece of the man behind the gimmicks: disciplined, intense, self-aware.

He wasn’t a showman who lucked into greatness — he was a craftsman who earned his moments the hard way. Clark might never have been the face on the lunchbox, but he was the guy who made you stop flipping the channel when you saw him.

If Deion Sanders was “Prime Time,” Bryan Clark was “Full Power.” He hit hard, played harder, and walked away before the business could finish him. That’s not failure — that’s survival.

And in pro wrestling, survival is the real championship belt.